The "origin" itself could seem to be an antithetical concept, something necessarily obviated by an embrace of this phrase, a (not so) simple extension of the parental role into the immaterial realm. But origins are never quite that. Their place, in language and in the arts, always finds itself occupied by the texts that find themselves woven of the stuff they're claimed to predate, before they could have known that this is what they were. No origin slips through without precedents, and no precedents content themselves as such; and certainly no text will sit silent and let itself be hermeticized. The relationship can never be father-child, between an origin and that which came of its origination; no, the text is always a virus, its woven cloth catching and unraveling, making all of what pretends to be itself into its own.

In 2006 Teairra Marí was posed to be Rihanna. Unfortunately, Rihanna happened. Marí now holds a semi-faceless presence, a precarious position at the bottom of the charts, being neither as marketable as Rihanna nor possessing her own fan-army, like her recent collaborators Gucci Mane & Soulja Boy. But before she was struck down, she struck out, with a single.

No Daddy is neither origin nor predecessor, neither of nor outside, #NoDads. They meet in the breath of a voice, in the slippage of the syntactic clarity. For where No Daddy structures itself as a revolt against a deterministic reading of the absence of the patriarch, #NoDads is an embracing of that absence's ineluctability. But from one, the other, and from the other, one; and so it is that No Daddy, despite striking long before the iron was hot, makes the right notes ring out, and holds them in suspension that we might see our own strikes before they happen.

And so I offer, here, a close reading of No Daddy, both song and video, in the hopes that things might become clearer. #NoDads is nothing, as yet; a simple phrase, one that finds itself displacing parts and occupying them, mutating certain cells within the whole and metastasizing their meaning. There will be no exegesis, not for now at least, not until the words take hold, the meme reproduced unto death; until then, we have only the power of creation, of adding meaning where it did not yet exist. And it is from within this non-origin, this perfect accident of an antecedent, that the words can be sprung to clear the space that is needed.

The video opens cold, with what is revealed to be a (day)dream sequence, of Teairra Marí confronting her mother about her new stepfather. It is, presumably, a recollection that serves as a prelude to the events of the video, but this is not entirely clear; it could, just as feasibly, be pure fantasy. A reading of the events of the video could be twisted one way or another depending on which stance one takes on this question; I will say, for the record, that I lean towards it being used as a recollection, but that either interpretation can lead comfortably to my reading, I think. The significant difference (barring the wildly boring reading in which the whole video itself is just Marí continuing to fantasize) turns on the gap between an actually pre-existing antagonism and a potential antagonism. In the case of the latter, the individualistic/voluntaristic threads would necessarily be pulled through more firmly, which I think is obviated by the moves toward solidarity and autonomy that the rest of the song/video seems to privilege.

If I might be allowed to skip ahead here, in order to further this argument and also note a certain thread that doesn't become clear immediately and, when it does, no longer seems to have any explicit relevance, another reason to disbelieve the supposition that Marí is idly (day)dreaming, or reacting to a potential antagonism, is the way that the narrative structure of the video incorporates the Dad Figures.

There are only, to my count, three Dads in this video; the stepdad in the opening sequence, the teacher that is introduced immediately afterward, and the Principal. By the time the video really kicks into gear, the Dads are (once again) absent, and the authority figures that are being struggled with are primarily female. Further, of these three Dads, none puts up any sort of fight - the stepdad merely parrots the mother and gets punched, the teacher shouts impotently and is pelted by paper, and the principal immediately succumbs to Marí's companion's seduction. If this video - and, I might self-servingly add, #NoDads - was about elevating a potential antagonism and working through it, then it would, presumably, be structured around that antagonism, and resolve with that antagonism. Because it is not the case that No Daddy or #NoDads describes, exclusively, a goal - it is not that an absence of Dad(dy)s is desirable, but that it exists.

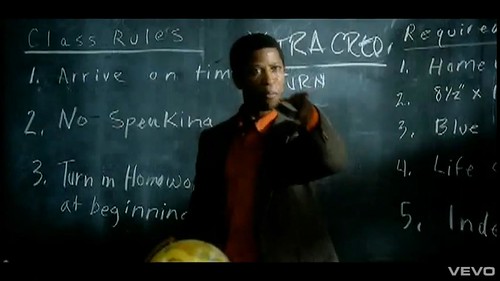

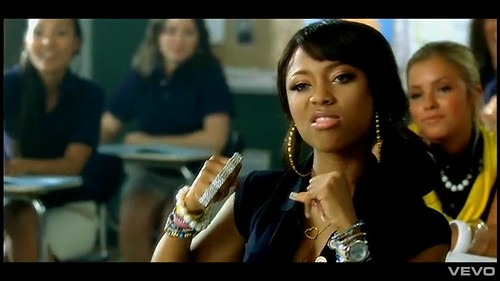

The classroom in which she has this dream is in a state of revolt. The teacher gesticulates wildly, screaming at the girls who are throwing wads of paper - or doing their makeup - at him, complaining from his position of authority, stationed in front of a chalkboard covered in rules, that he is being prevented from enacting that authority properly.

The teacher's rant is intercut with shots of Marí dancing in front of another chalkboard, this one covered in lyrics to the song she has not yet begun singing. This seems, fairly obviously, to be a playful inversion of the teacher's authority, in that it places Marí in a similar visual space but with certain key differences; namely, the words on the chalkboard change from rules to exhortations of dispossession & solidarity, and the lack of a podium or classroom remove both the mediation and subject/object relationship out of which authority arises. The juxtaposition of the teacher's wild gesticulations in front of his blackboard against Marí's fairly understated dancing also underline the disjunction of this visual metaphor. On top of this, the different demeanors that Marí effects, sitting in the classroom versus dancing in front of the blackboard, the one exasperated and antagonistic, the other self-possessed to the point of taunting, seem to indicate a working knowledge of the influence of both performance and structural positioning in the role of ongoing antagonisms.

That this consciousness of role-playing occurs during the stage-setting period of the video, between the "history" that the (day)dream represents and the insurrection that the video will shortly detail, along with cuts that make explicit where we are (such as the sign that establishes that we are in the "Wainwright School for Girls”) and who we (as viewers who are intimately tied to Marí's perspective) are opposing, is no accident; it even further embellishes the ways in which the established authorities of the school are merely actors. It is precisely this dialectical engagement with the arbitrary nature of authority that the video, and #NoDads, revolves around.

So when the teacher ends his rant with an upset, "Miss Thomas," (the biographical Mari's surname) "speak!" there is a bitter irony to his legitimation.

This irony is no hipsterization, however. And neither is it the reduction to the Imaginary, or a deference to the Big Other in some reductive psychologizing Lacanian fantasy. For while it is the case that the hyperbolic figure of authority is called upon to legitimate the voice of dissent, it does so precisely against the backdrop of a telegraphed appropriation of said dissenter for whom the privileges of the hipster or the analysand cannot exist. For both of these subjects come into being only in the presence of certain sets of social, economic, and cultural structures, and are defined by certain modes of reaction towards them. In the case of the hipster, this includes a combination of racial and sexual privilege which are valorized under the sign of social capital according to certain rules of rejection/negation; in the case of the analysand, it is the capacity to enter into the quasi-auto/theocratic environment which rejects/defers the messy circuits of exchange in favor of a purified structure of the mind, which it then works through.

Marí - and let's be clear here, we're talking about the fictional construct of Marí that the text of the song/video presents holistically, despite certain feints the text makes towards opening out onto the biographical subject, because no one believes them and no one is meant to, at least insofar as they gesture toward the cynical position that posits the fractured celebrity as a singular whole - does not occupy either of these positions. The autocracy of the classroom is ironized not as a cynical (and, therefore, universalizable) exemption, but according to the conditions of its reproduction. Which is to say, the exhortation, "speak!" tastes bitter because it is a speech act intended as both accession and curse, and yet we know that it is spat at a subject who both has no prior experience in the reproduction of the social structures that she is being cursed into (through the lyrics of the chorus and the (day)dream sequence) and who (therefore) does not even possess the capacity to reproduce that system properly (through the sequence in which she dances in front of the altered chalkboard).

This first chorus also introduces two important visual elements. The first is the replacement of the chalkboard sequence with a different extra-narrative sequence, in which Marí dances in front of yellow lockers in the hallways of the school with four back-up dancers. The second is the revelation that Marí brought some really rather pretty brass knuckles with her to class.

The first verse, also taking place in the classroom that finds itself in a sort of nascent-revolutionary state, is fairly rote, lyrically; it establishes Marí's authenticity, claiming that she has navigated special hardship, that she identifies herself primarily with her stance against authority ("I'm the type who don't give a damn about rules"). Its vague-specificity ("I was forced to survive on the streets / make my own way to eat / gotta do what I gotta do") that serves as a way of opening out doubly, serving either as an invitation for the listener to insert themselves into the the position of the narrator, or for the narrative position to be read biographically, to be followed up on to create the larger mythology of the pop singer. This opening out, however, as I've just stated, operates within the universe of pop music and celebrity. It is not, therefore, a lacuna within the text, but an invitation to overdetermine it however you'd like to. This distinction is crucial because, well, broadly, if you fail to grasp it then you are likely to wind up with an incredibly stupid reading of pop music, but specifically because it operates in the context of this video as a strong argument for avoiding the aforementioned reading in which the whole thing is a "mere" fantasy. Because the specific form this invitation to overdetermination takes is one in which the songs vagueness is asked to be read as being linked to determinate forms of struggle which it itself refuses to provide.

The verse, of course, does more than this, however. Its return to the extra-narrative space of the chalkboard dance sequence, in conjunction with its emphasis (while in the classroom) on foregrounding Marí's brass knuckles signifies that this is the moment in which it sets the terms of antagonism. Marí's singing "Been through so much" and "I'm the type that don't give a damn about rules" in front of the chalkboard might be read as a sort of stump speech, campaign promises from a candidate equipped (as we see within the narrative) for revolutionary violence. But these vagaries are, ultimately, more empty description than empty promise, and it is a strange fact of the video that, within the classroom, Marí is often decentered, with shots focusing on the girl brushing her hair, or the girl preparing another paper missile to pelt the teacher with.

That this subtle visual decentering takes place over ostensibly personal lyrics is negatively mirrored in the following prechorus; the lyrics shift from her individual story to words of solidarity and advice, while the visuals shift, in the first half, purely to the two extra-narrative spaces in which Marí dominates, and in the second half to Marí getting ejected from the classroom.

If these first four sections of the video, from the teacher's rant to the first prechorus, maintain the visual continuity of the classroom, then it could be said that this ends the first movement of the video. Marí's ejection thus completes the stage-setting portion of the video as the lyrics move for the first time from the individual narrative that they have so far made their focus to something less personal. But first, something must be said about that second extra-narrative space.

The sequence in which Marí dances in front of the yellow lockers prefigures scenes which we have not yet seen in this video, assuming we are taking it in in a linear fashion. Because, unlike the sequence in which Marí dances alone in front of the chalkboard, the set used in this dance sequence is recycled for the sequence in which the students at the Wainwright School for Girls take to the streets, so to speak; there are going, shortly, to be lots of semi-anonymous feet sprinting past these lockers, not just Marí and her dancers. But this sequence is still extra-narrative; even after the girls have begun running past these same lockers, this coordinated dance sequence still surfaces. That is, even after this space becomes subsumed within the narrative, given a particular location with respect to one of the three main staging locations (the classroom, the principal's office, and the cafeteria), it continues to operate as a space that exists outside of the narrative structure of the video.

Aside from being a visual trope, anchoring the space of the video firmly within the pop/R&B music tradition which dominated at the time of the videos release, this sequence functions as a sort of pivot point, by way of its shared space, between the spaces and actions of the video, and its mutilated temporality. There is an argument to be made, I think, that this sequence can be read as a sort of vanguard, as those who act before the time is right in order to guarantee the right time arrives, and also that it can be read as a sort of holdover, as those who continue to act even after the failure/success of the revolutionary moment. This is why it must remain outside of the narrative logic of the video, and also why it must be connected to it. As opposed to the chalkboard sequence, which posits a detourned and dethroned authority, the lockers and back up dancers signify a return to pop, and its degraded universal.

As Marí is kicked out of the classroom, there is an echo of the earlier invocation to speak; here again, this impotent authority figure is given some semblance of his power back, if only in order to facilitate that which was already predetermined to happen. For Marí was never not going to start singing, just as she was never not going to escalate this antagonism. But there is still that vestige, that performed deference, that qualifies and constitutes her actions.

With the second chorus, we finally exit the classroom and return only to the chalkboard. The opening shot, of the ejected girls' feet marching through the hallways of the school, seems a bit strange; it recalls 80s films about high school, when the cruel, popular girls enter the scene. The lyrics that overlay this visual, "I ain't had no daddy around when I was growin' up / That's why I'm wild and I don't give a (Huh)," also create a sort of dissonance. They aren't describing what you would expect to be hearing in that sort of filmic moment, but they aren't entirely divorced from it either; the "mean girls" characters are almost invariably the ones that end up (either sympathetically or humiliatingly, depending on whether the film tends more towards sentiment or cynicism) acting the way they act precisely through the revelation of "Daddy Issues."

The utility of this framing is immediately realized, of course, in the narrative, as the two girls who aren't Pop Stars distract the principal by flirting with him in order that Marí herself might sneak into his office. But, to linger for a moment on that shot, because it bubbles up out of the moments that precede it, and is subsumed by those that follow so elegantly, that it becomes something quite strange.

Those shots, of Marí and company walking through the hallway in formation, draw on the extra-narrative locker sequence with the backers; they draw on the (day)dream sequence with Marí's posture that seems so prim as to contain the potentials of an explosive violence; they draw on the performed assumption of power that the chalkboard sequence details. At the same time, they draw on this trope, of the bristling power of potential violence that operates by performing its own restraint that the "popular girls" signify.

This chorus, of course, also shifts the #NoDads content of this video from one in which it is explicitly antagonistic, as in the first chorus, if tacitly legitimated by who it intends to antagonize, to a more autonomous position. That lingering sense that the teacher still maintains some symbolic authority, in that he can act Marí into doing what she will do anyway, and thereby retain at least the position of authority if not uncontestedly enact its powers, is here destroyed. For that symbolic authority to maintain any credibility, in the absence of its ability to assert violence, it must at least be able to negate the possibility of retribution. With Marí's sneaking into the Principal's office at the end of the chorus, however, we see that this is precisely what is no longer going to be the case.

This second verse is, I will say it straight, my favorite part. And so I will lay absolutely bare how I see the sequence that it describes.

What is happening is that Marí, having seized the means of distribution, makes an announcement in solidarity with sex workers. The result of this, as shown in the shots of the girls in the hallways and classrooms eyeing the PA system approvingly, is an insurrection, in the form, at least initially, of a wildcat strike.

Now, couching it in these terms is obviously leaning in a certain interpretive direction, an indication that the interpreters center of mass is, perhaps, a bit closer to the spleen than the appendix, so to speak. But then, it seems incredibly difficult to disagree that this is, quite literally, what we are watching. No matter the language you choose, there is a stoppage, an exeunt, of those caught up in the moment of the dissolution of the status quo.

And it is here that the spaces of antagonism become articulated, that the particular classrooms in which this message strike home become visual, and so, according to the logic of the spectacle - for this is a music video, we must remember, a condensation and production of the spectacle, a product that is not bought or consumed, never itself exempted from the circuits of exchange because it never unfolds outside of exchange - and so become real. The computer lab, the tennis court, the science lab, the track. These are the four sites in which the seed of rebellion that Marí plants takes root.

The computer lab, where knowledge becomes digitized and commodified; where this school of girls can learn to type quickly, efficiently, can reproduce the pool of secretary. The tennis court, where physical fitness can double as the internalization of modes of social reproduction, where the ungainly accident of observable exhortation can be honed to a minimum of a grunt, while still keeping the physique and mannered form in proper 'shape.' The science lab, with its beakers and microscopes and candy-colored chemicals in dishes, that holds up the dual promise of progress (and all the wealth associated therewith) and a vestigial mysticism, that worst kind of academicism, that lets one peer through microscopes at possibilities, apportion them through eye-droppers, but never get close enough to play in; that give these girls the scent of what might better their situation, but never taste it. And the track, with its lone stretching figure seeming especially symbolic, almost transparently so, just taking a break from running in circles to hear what she needs to hear to sprint somewhere else, towards this new community of solidarity taking shape.

With the third chorus, the wildcat strike begins in earnest. The reintroduction of the chalkboard sequence anchors the scenes of the girls abandoning their posts, sprinting through hallways past lockers, some of which look suspiciously similar to those in which the extra-narrative dance sequence took place. When the chorus winds down, and Marí steps out from behind her seized means of distribution, leading the girls past the blue lockers that seem (according to the shot structure) to be leading toward the yellow lockers that were danced in front of - and the fact has been established that the girls are not just refusing their labor, not just sprinting through the halls, they are actively striking, barricading the teachers into classrooms - then, well, then we have come to the point we've been building to so far, with only one revelation still in the wings.

It is, of course, this spatial convergence that the camera is urging us toward that is itself the final revelation. The final space.

If the visuals that accompanied the previous prechorus articulated the spaces of antagonism, then this chorus is the process of collapsing them into each other. As the objects of the antagonism take flight into a communal space, the spatial alienation resolves itself; no longer are these girls atomized, broken into arbitrary groups of commodified instruction (it would be hard to believe that the “Wainwright School For Girls” was anything other than a private school, but even if it wasn't, well, if you don't believe public schools are in the business of commodified-knowledge-production/distribution, then I'm pretty shocked you've ever heard of me and made it this far), but instead are, again, escalating the antagonism, not by addressing them individually, but instead by converging them all, in space.

If you have guessed, by now, that the final revelation, the collapsing antagonisms into a unified space, that occurs at the end of this bridge, either by my own language so far or by watching the video, is an occupation – specifically a closed or locked-down occupation – then we're on the same page. Here it is, in its full glory; a pop song, about the absence of the patriarch, which tracks a path of rebellion through the wildcat strike, inspired by seizing the means of distribution (the PA system) and making an announcement in solidarity with sex workers, to an occupation of the only means of reproduction that the school possesses – the cafeteria.

Schools are themselves the premiere sites of reproductive labor within contemporary capitalism. They are social factories, as the saying goes, whose nominal goal, the egalitarian dissemination of knowledge, is only of course a cover, or at best an ideal, which provides a moral cover for the real work of socialization which goes on there, the reproduction of systems of class power. #NoDads, of course, has this particular function as its central concern, the father having always been the symbol not of the fact of reproduction, but its labor; this labor is itself almost always relegated to the women, being most often thought of as housework and birth, but it has always been the figure of the father who carries out, primarily, what we might call immaterial reproductive labor. The absence of the dad is the absence of the coercive and exploitative relation of the reproduction of the social.

Insurrection must follow these lines of flight. From the classroom, where the father-teacher rages at his unperformable authority, which crisis we must facilitate; to the hallways, where the atomized might meet in the synchronized, (dis)ordered stomping of feet toward a goal that perhaps none quite yet know; to, finally, the cafeteria, where the real production of reproduction, both the simple fact of eating, sustaining the body, and the complex fact of the network, where the biopolitical administration of class difference can be enacted through self-management, and where, having both experienced and enacted #NoDads, a community of bodies can be created.

The single most important visual component of the third and final prechorus is the reintroduction of the second of the extra-narrative sequences, the dance in front of the lockers. This is where, as I said earlier, it becomes incontestable that this sequence is in fact extra-narrative; the girls sprinting in front of these same lockers do not encroach upon the sequence, even though at one point there is a cut directly from the girls running to the dance sequenced. And as I mentioned before, I believe the importance of this sequence is its status as a pivot point.

As the occupation of the cafeteria begins in earnest during this prechorus, the return of this pivot point is crucial. What makes the two extra-narrative sequences extra-, of course, is a sort of atemporality - they both exist outside the time of the narrative. The chalkboard sequence also exists outside of the space of the narrative, however, which places it more as commentary, a sort of eschatological projection, than the other sequence.

That which occupies the same space, but is disjunct from time; in other words, a tradition. As I've said, this sequence is what anchors No Daddy to the tradition of pop/R&B videos of the particular moment in which it was made. And so it is that the simple juxtaposition that the video revolves around becomes fully realized.

It is the relation of pop, with its insistence on the bodily, on the disruption of the disembodying of taste, to the direct action, with its insistence on disruption, on the immediate embodying of politics, that is being juxtaposed. And it is done so under the sign of absence of the figure of immaterial reproductive labor.

This is the universality of pop, that it is timeless and of space, as though it were itself a tradition, as though it were itself a history. Its space, though, is always constructed, is always a set, is the club that never quite has a referent; it is always an ahistory.

The end of this song, as the beat fades out to the images of the occupied cafeteria and Marí dancing in front of the chalkboard, neither affirms nor denies the potentiality of the moment that Marí has activated with this song, whose time would not even begin to come to pass until over half a decade later. But this is precisely the point; that the pop, whether it divides itself into four fourths or signals the beginning reintegration of the apparently disparate system, is without time, and thus, without ancestry.