Animal Crossing: Amiibo Festival is the perfect videogame. Perfect, at least, in its simulations. It's a board (video)game, which means that it is a boring slog, a barebones structure by which to stimulate sociality. The vulgar materialism of Amiibo lines up perfectly with the parodic Stalk Market and the fan infatuation with the Villain Tom Nook, rentier capitalist. The simulations are of systems as much as economies; so much pretends to skill. Amiibo Festival dares you to engage, knowing it won't satisfy. The secret's that it wants you to engage with each other, not it.

Porpentine and Neotenomie's 3D Twine game Bellular Hexatosis feels as though it could be an experiment or a zenith; the marriage of Myst-style point and click with Twine is pleasingly odd, but it's hard to tell where it goes from here. With Kitty Horrorshow's increasing adoption of in world text, though, the possibility is certainly there.

The story itself crests slowly and is somewhat underwhelming in its brevity, but Porpentine's mastery over the intentional misfires of moment-to-moment prose is on full display. The hub area is also a good touch; you move in circles to begin, which gives both space and momentum. Touch mushrooms and talk to eyes, it's good.

Way to Go is an interactive experience, shot on 360° video, and funded by the National Film Board of Canada. The experience is of moving through space with an avatar. The space is a real forest that becomes abstracted over the course of the experience; the movement is of walking or running or flying along a track, or of stopping and watching.

The way Rez looms over on-rails games highlights their affinity with visual abstraction; Way to Go's triumph is leveraging that in a way that combines it with a reflective experience that doesn't bow to flow.

The danger of Walking Simulators is that their laying bare of the mechanisms of spatial abstraction in videogames becomes tied to their affect. Per Austin Howe (interpreting Zolani Stewart), the Walking Sim is characterized by "drama, dread, and loneliness." I agree, especially with the dread. What, then, is the consequence of this yoking?

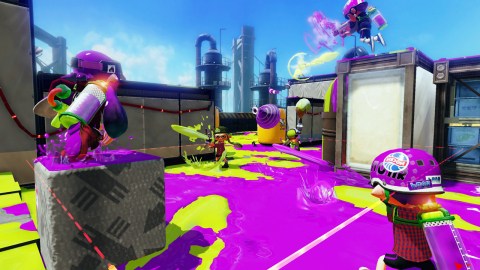

My hope, at least, is that it doesn't refuse us the possibility of acknowledging Splatoon's contribution to our understanding of spatial abstraction. Not just in its appeal – shooting the space instead of the people – but in its design from the ground up. From fashion to level and weapon design to absenting voice chat, Splatoon is an expression of the joy of virtual space.

If merritt kopas' graphical games can be crystallized into one thing, it would be the use of the down arrow key. Shattered out, it becomes her manifesto of late last year or her Soft Chambers work throughout this one.

Obéissance, specifically, is about navigating a small environment repeatedly while reading the words of Simone Weil on consenting to obedience to God. I've called attention to her animations before, but Obéissance might have my favorite (the toe tapping!). It would be easy to praise the thematic resonance, but, like wrestling, what sets it apart are the little things.

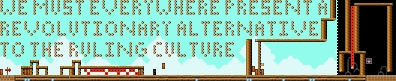

I've developed a bit of a morning ritual, where I play/watch Automatic Mario levels as I eat breakfast. There's a nice rhythm to juggling the Wii U Gamepad and a plate of food, as Mario skillfully avoids dangers and hits sound cues. That Super Mario Maker also lets me engage in pseudo-Situationist praxis is, in some way, all I've ever wanted.

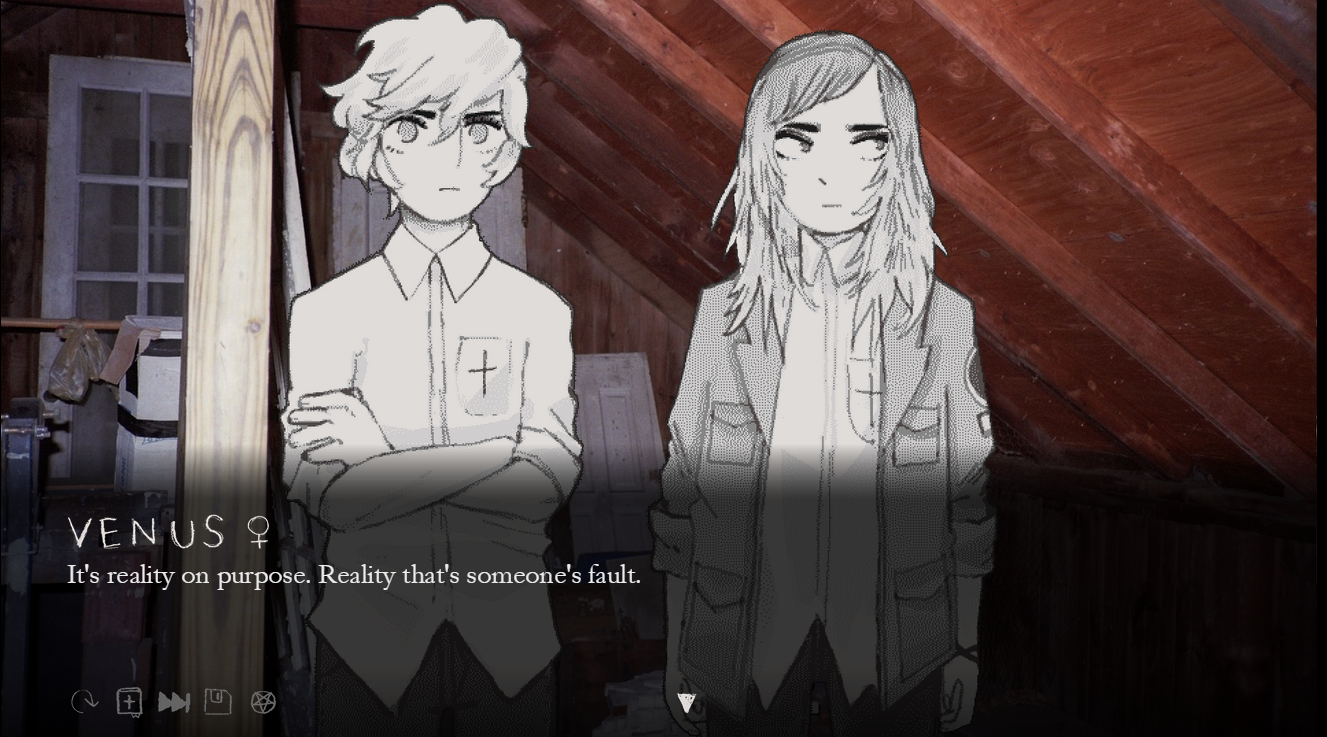

If you make two choices a certain way, the ending scene of Trigger includes an extra snippet of internal monologue, where Wendy removes a key from her hand and reminds herself that she will likely never know what it is for. I read this as a kindness, given the choices made.

There are aspects of Trigger that I suspect might not work, but moments like with the key bring it into focus. As a story about people, Trigger is a minor masterpiece.

If there's one aspect of videogames I'm going to wax poetic about some day, it is their axes. Horizontality is the fundament; verticality I find endlessly interesting. Downwell, then, has an obvious hook. That I've probably spent more time in 2015 playing Dungeon Crawl: Stone Soup than anything else also helps. That waxing can wait for another day, though; Downwell is still about the satisfaction of chaining combos for now, and it's incredible for that alone.

It seems impossible to overstate the work Robert Yang has done over the course of 2015, and Stick Shift stands partially in the stead of Succulent and Cobra Club and Rinse & Repeat, all incredible. If anything, the post-mortem seals Stick Shift's importance; it is political in a way that games have refused to admit themselves to be.

There is also a certain awkwardness to Stick Shift, in its representation of action – that is, its controls – that endears it to me especially. It's an awkwardness that makes stroking the shifter feel particularly good.

That, and ACAB.

In my review of We Know the Devil, I tried to highlight how the Christian Summer Camp Horror Visual Novel is properly Brechtian in its popularity and realism (see p2). I don't know that I sold many people on it. That's okay, but I also would like everyone to play it.

Even if I feel like "videogame writing" is the easy mark, We Know the Devil shows just how often it fails; not as craft, but in its capacity to universalize important political knowledges. I later said that its collectivity is one of the more important videogame things ever. I stand behind that, and the fact that We Know the Devil is a superbly crafted story only adds to it.